According to the Nashville Tennessean, Kathleen Lisle cannot forget the summer day a priest at Christ the King Catholic Church called her childhood home, asking her to help fold bulletins for Mass.

She hesitated to go.

Lisle was 12. She did not want to be alone with the Rev. James Arthur Rudisill, but, in the 1950s, explaining that to her mother seemed impossible. A frequent guest at the Nashville home where she grew up with 10 brothers and five sisters, Rudisill sometimes sat next to Lisle, rubbing her leg while playing chess.

At her mother’s urging, Lisle walked the few blocks to the parish church.

“He was kind of touchy while we were doing that and then afterwards he said, ‘I need to go over to the school,’ ” said Lisle, who asked to be identified by her maiden name. “I was afraid to go, but you heard back then, ‘Do whatever father tells you to do.’ So I went.

“He took me over to the gym and up on the stage to the closet on the right-hand side and that’s where he molested me.”

It would take Lisle about 40 years to find the courage to report the sexual abuse to the Roman Catholic Diocese of Nashville. Nearly a quarter of a century would pass before the diocese would make the allegation against Rudisill public.

Diocese releases names, but critics think it can do better.

The Nashville diocese is one of about 60 across the nation to release the names of accused priests they have long kept secret — in some cases for decades.

The names have rolled out in news releases and newsletters since a Pennsylvania grand jury investigation in August laid out in detail the “horrifying scale” of sexual abuse perpetrated by 300 priests on more than 1,000 identified victims spanning nearly eight decades.

Rudisill, who died in 2006, is among the 21 clergy the Nashville diocese has named since November.

The diocese published the names because of its commitment to transparency, accountability and pastoral care, said Rick Musacchio, the diocesan spokesman. The diocese reviewed its files to compile the initial list and has added to it as more information becomes available from other dioceses and religious orders, he said.

But critics of the church, among them abuse survivors, longtime church members and the Tennessee chapter of the victim advocacy group Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, say it’s not enough.

They have asked for an independent investigation. In at least 18 other states, attorneys general have begun investigations. In at least four states, dioceses have opened up their files to independent consultants to conduct a review. Among them:

In Illinois, the attorney general issued a scathing report that identified more than 500 clergy who had not been named in the church’s own disclosure of accused priests. The Illinois diocese had identified 185 clergy with credible sex abuse allegations against them. The attorney general identified 690.

In an independent review in Arkansas, a consultant found credible sexual abuse allegations against 17 priests and four members of religious orders — five more than the Arkansas diocese had found on its own.

The attorney general of New York has announced he would work in tandem with district attorneys to investigate abuse allegations.

West Virginia’s attorney general is relying on state consumer protection laws to pursue an investigation. In Tennessee, Attorney General Herbert Slatery has declined to open an investigation, saying he lacks the authority. Musacchio said the diocese may consider hiring an outside reviewer.

Without a full and independent investigation into clergy sex abuse in the Nashville diocese, and with decades of secrecy by officials, victims and their advocates say there can never be a full reckoning within the church.

They point to the dismissal from the ministry of a Nashville deacon who is demanding an independent review and the bumpy rollout of the list of accused priests.

Initially, the diocese released the names of 13 priests accused of abuse, misidentifying one priest as deceased and omitting assignments for some of the men. By March, the number had grown to 21 as more details emerged and the names of clergy connected to the Nashville diocese appeared on other lists. None are serving in active ministry.

Susan Vance, a leader of the Tennessee chapter of Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, said more than 100 victims have come forward to her group. The most recent was a man who contacted Vance in early January, she said.

“If we ever got an investigation, people would come out,” Vance said.

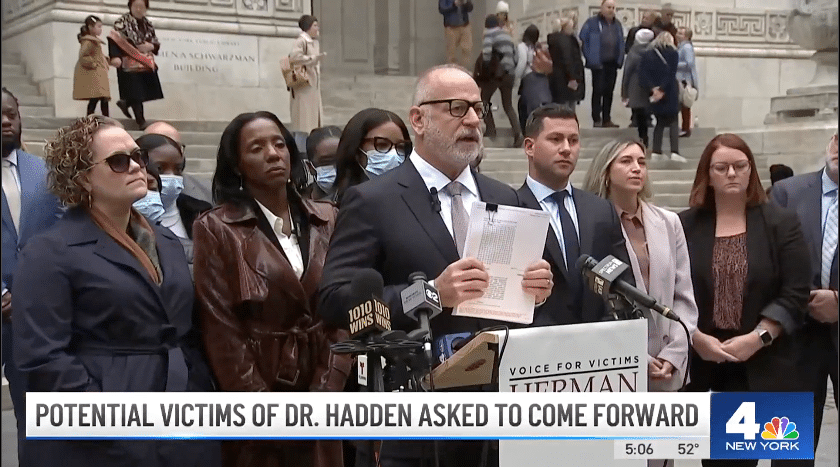

“Sadly, the cover-ups continue,” said nationally recognized sex abuse attorney Jeff Herman. “The sexual abuse of children continues. We need transparency. These predator priests and their enablers must be exposed,” said Jeff.

Over the past few months, Catholic Dioceses across the state of New York have released hundreds of names of accused priests. This includes the Roman Catholic Diocese of Albany, Diocese of Brooklyn, Catholic Diocese of Buffalo, Roman Catholic Diocese of Ogdensburg, Diocese of Rochester, and Roman Catholic Diocese of Syracuse.

In 2019, New York passed the Child Victims Act that will allow for action to be taken. Under the new law, victims of child sexual abuse in New York will have a one-year window beginning August 14 to file a lawsuit no matter when the abuse occurred.

“This is the beginning to resolving decades of corruption that have traumatized so many,” said Jeff.