According to The Los Angeles Times, for decades, the Boy Scouts of America has closely guarded a trove of secret documents that detail sexual abuse allegations against troop leaders and others.

The most complete public accounting of the abuse so far came in 2012 when the Los Angeles Times published a searchable database of 5,000 files and case summaries that are part of the Scouts’ blacklist known as the “perversion files.”

Seven years later, more details are emerging about the scope of sex abuse in the youth organization. A researcher hired by the Scouts to analyze records from 1944 to 2016 testified earlier this year that she had identified 7,819 suspected abusers and 12,254 victims.

But even those numbers grossly understate how many molesters infiltrated the Scouts’ ranks over the years, according to lawyers who have sued the organization on behalf of hundreds of abuse victims. Most predators were accused of abusing multiple boys, they noted, and many instances of abuse were never reported.

The Boy Scouts of America has grappled with years of costly litigation at the same time it has struggled with declining membership. The organization says it is considering bankruptcy protection, which would halt ongoing lawsuits while settlements are negotiated.

Seattle attorney Timothy Kosnoff, who has sued the Boy Scouts more than 100 times since 2007, said he and two law firms he had teamed with recently signed more than 350 new clients through a national TV ad campaign and a website, Abused in Scouting.

Kosnoff says the allegations span decades and 48 states, and are made by victims ranging in age from 14 to 97. Most of the accused — 234 — are men who are not named in the blacklist, which the organization has used to exclude suspected molesters.

“Consequently, the number of children who have been abused in Scouting is much larger than the BSA has ever disclosed,” Kosnoff said. “Abused children suffer these wounds for a lifetime. It is time the BSA is held to account fully for this atrocity.”

The magnitude of the Scouts’ abuse problem takes on new significance as New York and New Jersey extend their statutes of limitations on child sexual abuse lawsuits, opening the 109-year-old youth organization to a potential slew of new claims. Similar legislation is pending in California.

National Scouts officials will not say how many sexual abuse lawsuits have been filed against the group or how much has been paid out in settlements and judgments, and no reliable independent estimates exist.

In a statement to The Times, Scouts officials emphasized enhanced youth protection measures now in place, including criminal background checks for Scout leaders and volunteers, and said that 2018 produced only five known cases of sexual abuse among the ranks of 2.2 million Scouts.

“We care deeply about all victims of child abuse and sincerely apologize to anyone who was harmed during their time in Scouting,” the statement read. “We believe victims, we support them, and we pay for unlimited counseling by a provider of their choice and we encourage them to come forward. As soon as the BSA is notified of any allegation of abuse, it is immediately reported to law enforcement.”

The tally of more than 7,800 suspected abusers identified by the organization’s expert includes some who applied but were never allowed to join the ranks, the Boy Scouts said. The organization would not elaborate.

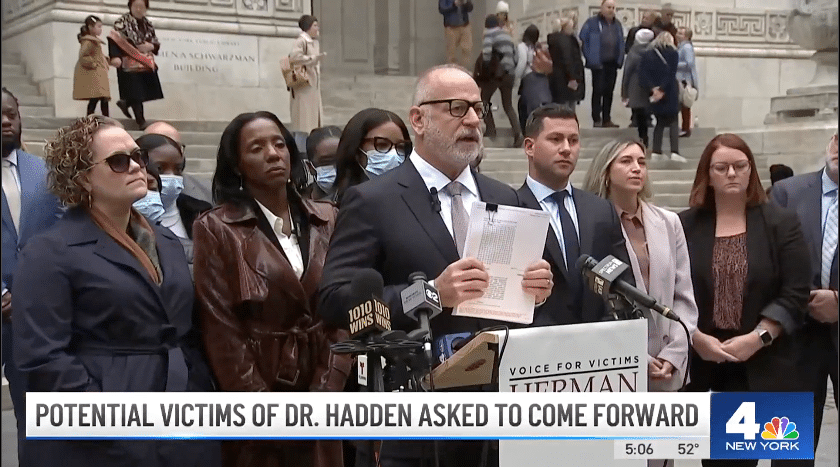

The number was cited at a Manhattan news conference held in late April by attorney Jeff Anderson, who described his “shock and dismay” at the scale of the abuse but said in a subsequent interview that he believed the figures were on the low side.

“It’s emblematic of how little is actually known about the magnitude of it,” he said.

Anderson first learned of the figures while handling an unrelated sexual abuse lawsuit in his home state of Minnesota. Among those testifying in the case was Janet Warren, a professor of psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences at the University of Virginia, who said she and a team of computer coders came up with the tallies after spending five years analyzing files under a contract with the Scouts.

The numbers are flawed because many perpetrators had multiple victims, many instances of sexual abuse are never reported, and the Scouts have acknowledged destroying an unknown number of files over the years, said Paul Mones, one of the lawyers in a landmark Oregon lawsuit that resulted in a nearly $20-million jury verdict against the Scouts in 2010.

He said fewer than a quarter of his Scouts abuse cases in the last 10 years had involved perpetrators who were in the files.

Formally known for years as the Ineligible Volunteer files, the dossiers — now called the Volunteer Screening Database — name suspected abusers from all regions and contain biographical information, legal records, official correspondence and boys’ accounts of alleged abuse by Scout leaders who often were respected members of their communities. It was not necessary to be charged with a crime to be placed in the files, nor were all allegations substantiated.

The records have been kept for about a century. Their publication by The Times in 2012 triggered lawsuits by abuse victims who cited them as evidence the organization knew of pedophiles in their midst but failed to protect children.

Scouting officials have fought hard in court to keep the files from public view, contending that confidentiality was necessary to protect victims, witnesses and anyone falsely accused. They also say the blacklist has been effective.

“While some perpetrators were able to circumvent the system, the fact is that there were countless times when the files successfully prevented perpetrators from joining or rejoining the organization,” according to the Scouts’ statement.

The Times’ yearlong examination of the files seven years ago revealed serious flaws in the group’s efforts to stem abuse.

In hundreds of cases, the newspaper found, the Boy Scouts failed to report offenders to authorities and often hid the allegations from parents and the public. In more than 125 cases, men allegedly continued to molest Scouts after the organization was first presented with allegations of abusive behavior.

More than 100 times, officials with the Scouts actively sought to conceal the alleged abuse or allowed the suspects to hide it. Scouts officials sometimes urged admitted offenders to quietly resign and then helped cover their tracks with bogus reasons for their departures.

That finding was starkly at odds with Warren’s conclusion, after reviewing the files, that there was no evidence of a cover-up by the Boy Scouts of America. In its statement, the Scouts said Warren was referring only to any cover-up at the national level.

“There have been times, most of them decades ago, when local individuals did not follow reporting procedures — either to the national organization or to law enforcement,” it said, noting that in 2013 it reviewed its files and notified police of any instances of abuse that might have gone unreported.

The Times obtained the records for its database from Kosnoff, the Seattle attorney, and from the court-ordered release of files from the landmark trial in Portland, Ore., in which a former Scout accused the organization of failing to protect him from a predatory leader. The $20-million verdict, most of it for punitive damages, marked a turning point for the Scouts, which until then had quietly settled most such lawsuits, Mones said.

The files’ publication contributed to a “fundamental shift in the national consciousness about sexual abuse in large institutions,” he said, which also was driven by scandals at Penn State, USA Gymnastics and the Catholic Church, among others.

The result helped prod a new awareness by state legislatures to reform their statutes of limitations.

This week, New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy signed legislation allowing those who were victimized as children to sue until age 55 or within seven years of discovering that the abuse caused them harm. New York also has passed a law with similar provisions and a “look back window” that would allow some old claims to be revived.

A California bill working its way through the Legislature would expand the statute of limitations for victims of childhood sexual assault to sue for damages, raising the maximum age to file an action from 26 to 40, or within five years of discovering harm from the abuse.

The Times’ publication of its database fueled a tsunami of civil litigation against the Scouts, Mones said. He estimated that at least 400 lawsuits had been filed since the files’ release and noted the Scouts had sought to settle many other legal actions before they were filed.

At least two of the organization’s insurers have refused to cover the payouts, contending that the Scouts could have prevented the abuse that led to the claims.

Although the national organization still has assets of more than $1 billion, the looming liabilities are large enough that it is weighing whether to file for bankruptcy protection. A Chapter 11 filing would require new claims of abuse to be handled in that venue rather than in state courts. Those filing claims would join other creditors.

Some Catholic dioceses caught up in the church’s sex abuse scandal employed the same tactic.

“The BSA is considering options to determine how victims can be equitably compensated while the organization continues with its mission to serve youth,” the Scouts’ statement said. “No decision has been made.”

“There are many similarities between the Boy Scouts and the Catholic Church in dealing with known predators,” said nationally recognized sex abuse attorney Jeff Herman. “Scout officials did not go to the police and expose the truth of what was going on. The abuse was covered up,” said Jeff.