When Pennsylvania resident Patty Fortney-Julius took to the microphone at a New Jersey Senate Judiciary Committee meeting in early March, she had a clear request: Pass a bill that allows more child sex-abuse victims to sue, a step she and her sisters said is crucial for finding justice.

“It’s heartbreaking to us that the state of Pennsylvania has gotten it all wrong as they continue to put pedophiles and the institutions that cover it up before the victims,” Fortney-Julius said. “We implore you, as representatives of the great state of New Jersey, to not make the same mistake and to get this right today.”

As she and her sisters have done so many times in their home state, Fortney-Julius told their story. She told the committee of her family’s excitement in 1982, when they learned that a priest from New Jersey, the Rev. Augustine Giella, had been selected to run their church, St. John the Evangelist in Enhaut, part of the Harrisburg Diocese.

And then, her voice beginning to tremble, she recounted the time Giella took her and her siblings to a motel in Wildwood, and how he abused one of her younger sisters. The trip, she said, “will haunt us forever.”

On Monday, New Jersey passed a bill that will allow the Fortney sisters and others like them to sue. New York also passed a measure, and similar changes to statutes of limitation are up for consideration in Maryland. Democrats have majorities in all three states.

In Pennsylvania, where Republicans control the agenda, the legislature has been paralyzed. “This is not a political decision,” Carolyn Fortney, Patty’s sister, who also testified in New Jersey, said during an interview Friday. “I think it’s so disheartening when we hear people say, ‘We need a blue wave movement to do this.’”

“This should be a bipartisan issue,” she added, noting that her family includes Democrats, Republicans, and independents.

Like their counterparts in Pennsylvania, New Jersey lawmakers had jockeyed for years over whether to change the statute of limitations. New Jersey State Sen. Joseph Vitale, a Middlesex County Democrat, said he began pushing for changes nearly 20 years ago, when “some of my colleagues who no longer serve with me looked at me like I was insane.”

There was a wave of enthusiasm in 2002, after the Boston Globe’s reporting on sex abuse in the Roman Catholic Church ignited a wave of activism around the globe. But the church, too, lobbied hard, as did some in the insurance industry. In the years since then, the New Jersey governor’s office has changed hands four times, and many seats have turned over in the Legislature.

Then, last summer, the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s Office released a report that singled out more than 300 “predator priests,” including some with New Jersey ties.

New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir S. Grewal, a Democrat, created a task force to investigate clergy abuse and its potential cover-up in Catholic dioceses there. The dioceses, meanwhile, created a victims’ compensation fund, with a caveat that anyone who takes money through the program must agree not to sue.

The grand jury report “put a real spotlight on the issue and really reminded my colleagues just how much of a pandemic this is, and I received several calls from my colleagues, unsolicited, asking to be cosponsors of the bill,” Vitale said.

When Vitale introduced the latest version of his legislation this year, the Senate’s deputy majority leader, Nicholas Scutari, a Union County Democrat, signed on as a prime sponsor.

The bill extends the statute of limitations for civil cases from age 21 to 55, or seven years after victims discover that their childhood sex abuse has contributed to problems in their lives. It also opens a two-year window that allows people whose cases are outside the statute of limitations to sue. It is currently before Gov. Phil Murphy, a Democrat, who is expected to sign it.

The grand jury report also spurred a wave of activism in Pennsylvania, where victims encouraged legislators to make changes recommended by the grand jury, such as extending or reopening the statute of limitations.

Lawmakers came close last fall, but the effort stalled after Senate President Pro Tempore Joe Scarnati (R., Jefferson) introduced an amendment that would have allowed some older victims to sue their attackers — but not the institutions that might have covered up the abuse.

The session ended without a compromise, meaning the legislation had to start from scratch in 2019.

For a while, it was quiet.

Senate Democrats announced plans earlier this year for a bill that would abolish the criminal and civil statute of limitations for future sex-abuse cases and create a two-year window in which people whose cases are time-barred can sue. They are expected to introduce that bill next month.

On the House side, two representatives who both survived child sexual abuse themselves — one a Democrat, the other a Republican — have partnered on a pair of bills aimed at changing the statute of limitations.

One bill would make changes for future child sex-abuse victims, increasing the cutoff for when they could sue from age 30 to 55, and eliminating the criminal statute of limitations for some sex offenses. The other would change the state constitution to create a two-year window allowing child sex-abuse victims whose cases are outside the current statute of limitations to sue, regardless of who abused them. Both are sponsored by Rep. Mark Rozzi (D., Berks), who has been one of the Capitol’s most vocal advocates for changing the statute of limitations, and freshman Rep. Jim Gregory, a Republican from Blair County. Rozzi did not respond to messages seeking comment.

For Gregory, the constitutional amendment fulfills a campaign promise. But it’s also personal. He, like Rozzi, said he is a survivor of child sexual abuse.

“It’s more than just the statute of limitations and compensation issues,” Gregory said. “It’s about trauma and abuse and bringing it out in the light.”

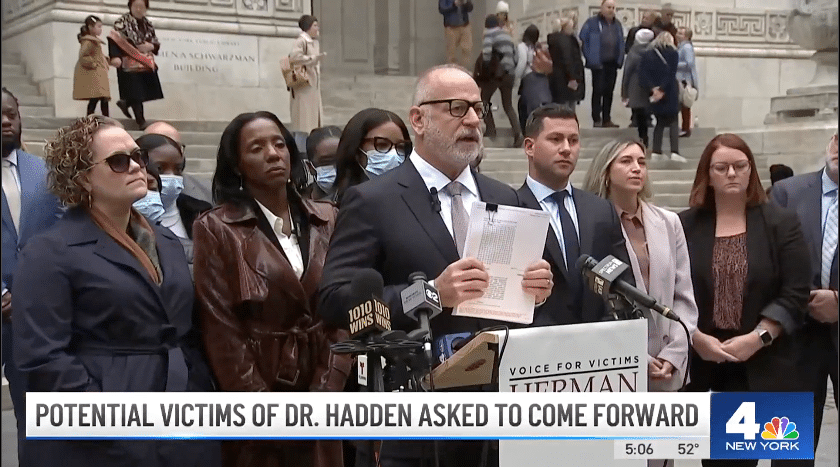

“These traumatized children and adults deserve to share their stories and find healing,” said nationally recognized sex abuse attorney Jeff Herman. “It’s not only for them, but to empower other victims who are too afraid to come forward,” said Mr. Herman.